Recalling Vietnam - by profmarcus

For a few short years, several lifetimes ago, I wore a uniform.

(more)

PLEIKU

The Axe Falls

Shortly after the first of the year, 1968, the axe fell. Hard on the heels of my 1-A draft status came a notice to report for a physical. I wasn't drafted yet but the hounds were sniffing at the door. Being as how, at the time, they were drafting for the Marines and, being as how there was absolutely no way in HELL that I was going to be a Marine, I took myself down to the friendly Army recruiter to see about enlistment. Since I had been working part-time as a radio announcer and tv cameraman, I had this wonderful mental picture of information specialist school at Ft. Benjamin Harrison followed by a fabulous career on Armed Forces Radio. HA! I was not the only one with that idea, it seemed. The best I could hope for, I was told, was clerk school. "Oh, well," I thought. "At least I'll learn to type."

Basic

In early March I kissed my mother good bye, got on the bus to Denver where I was sworn in, spent the night at a cheap hotel on the Army’s nickel, and flew off the next day to Army basic training in Texas. Eight weeks of what was, for me, total hell followed. The training regimen and barracks life were twin nightmares. I had never been in the best of physical shape so, besides very real physical pain, I also had to endure outright humiliation like the time I was dragged along between two lieutenants on the mile desert run. Or the night I instantly jumped up from a dead sleep about two a.m. blinded by the pain of a cramp in my calf. Severely slamming my head on the upper bunk in the process, I then proceeded to jump madly around on one foot, all the while trying to pound out the cramp and shrink from the snickers of those I had awakened.

Basic training field site

As if that wasn't enough, the constant verbal abuse from the drill sergeants pushed me to the edge of desperation. I needed to get OUT and fast. Maybe others could shrug it off but I was dying inside. I went to see my company commander and told him I was gay. To this day, I haven't the slightest idea what possessed me to say that. If I had said I was contemplating suicide, I would have very likely been home within days. I certainly can't claim I was thinking clearly. I just wanted a ticket outta there. I detonated my little bomb with the Company Commander, a captain no more than three years my senior, after telling the Drill Sergeant that what I needed to tell the Captain was "too private" and "too embarrassing" to share with him first. Within what must have been record time, I found myself in the waiting room of the Mental Hygiene clinic. (Leave it to the military to coin a term like "Mental Hygiene!") The therapist subjected me to what I later learned was the MMPI, the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory, a pathology-focused assessment instrument, and a series of Rorschach ink blots. I have no idea what they found out nor do I have a clue about what they were looking for. All I knew was that, in an era long before “don’t ask, don’t tell,” I was whisked back to my company where, instead of cleaning latrines, I was assigned to read the newspaper every morning in the dayroom, cut out articles I found interesting and post them on the bulletin board. With the speed of the jungle telegraph, I became the most envied man in the company. Yeah, Ok, I lied. And since I had told them I was aroused by watching the other guys shower, they must have figured out that this would keep me out of harm’s way. What tangled webs we weave!

A major realization dawned during those sand-blasted eight weeks, so major that it forever changed the essence of my world view. The entire purpose of military basic training is to remove everything that marks you as an individual, to break you down and then build you back up as a "soldier," someone who will take an order and say, "Sir, yes, SIR!" Your hair gets cut off, your clothes are taken away, the uniforms all look the same, you can't wear anything that isn't "authorized," you all eat the same food in the same place at the same time, you all sleep next to each other in rows of identical bunks, you all speak the same lingo, you all shit and shower together, you all follow the same rules, you all complain about the same things. There's only one way to tell people apart and that is to pay attention to what's coming from the inside - how they talk, how they think, what they say, what they laugh at, what pisses 'em off, what they get passionate about, what they regard as fun, how they treat other people. Up to that point, I had, without thinking, made most of my judgements of those around me based on externals. In basic training, that was no longer possible. The "externals" were gone. I had to find another way.

Advanced

Clerk school in Arizona followed. I had made a few good friends in basic, hippie wannabes, and it was with them that I was introduced to getting high. Since the base was only a stone’s throw from Mexico and with weekends free, two months of training drifted by in a cannabis haze. Flirting with severe punishment for AWOL, I even flew home for a weekend. Most distressingly, however, my friends were all national guardsmen. I had no doubt been attracted to them because, among the other recruits, they were clearly the more intelligent ones. They were getting their training before heading back to school, jobs and normal lives. They knew that, when the training was through, they were going home and I wasn't. They felt bad for me, sure, but... I was terrified that Vietnam was going to be my next stop. The suspense was unbearable. Three weeks of school left, two weeks, one week. When the orders finally came down, my friends looked at me like I had just received a death sentence. "At least I'm not in the infantry," I consoled myself.

Arizona sunrise, advanced training

On the Way

The events surrounding my departure for Vietnam are as clear to me now, thirty-seven years later, as though they happened yesterday. As with most memories, they seem to come bunched in little packets, miniature vignettes that somehow capture the essence of the moment.

• My mother and brother drove me to the Denver airport. I was excited because I was going to be flying on a TWA Boeing 707, the flagship of the new jet age. I was even more excited because it was coming from Zurich via Washington D.C. and on to San Francisco. I was going to be flying on an international airline onboard a plane that had just flown across the Atlantic Ocean!

• My good friend, Bruce, met me in San Francisco. We had decided we would spend a few days together before I took off to that dark place where people were dying. We ate, drank, and laughed. It was especially poignant when we said our goodbyes as he dropped me off at the Oakland Army Base.

• The Oakland Army Base was little more than a giant warehouse where wet-behind-the-ears army boys, fresh from hugging their mothers and kissing their girlfriends, were stacked, awaiting the call to the bus that would take them to Travis Air Force Base and the flight to Vietnam. I located a friend from advanced training and, true to form, we somehow managed to collect enough dope to smoke a giant number rolled in toilet paper. From this drug-addled, surreal view of our surroundings, the following image was burned into my brain: two friends, sitting side-by-side on a bunk, one reading Bible verses to the other in an attempt to ease the fear of what was to come.

• It was almost midnight when my group was called for the bus. Tired, tense, frightened, wired, and still high, I remember running across the tarmac at Travis at 2 a.m. under the moon and stars with a warm wind blowing, yelling and whooping, racing for the stairs of an Evergreen DC-8 that would take us to our fate. The plane was minus a first class section; only open seating, six across from front to back. Ironically, I noted that officers and senior enlisted men were already on board, seated up front. They could have been creatures from another planet as far as I was concerned. I dashed for and got a window seat.

• After re-fueling stops in Anchorage and Yokota Air Base, Japan, each equally and enticingly foreign in its own way, we crossed the coast of Vietnam in late afternoon. Everyone was jockeying for a view out the window. There it was, strange, mysterious, deadly, the stuff of Time Magazine and the evening news. What would befall me there? The plane descended from cruising altitude in steep circles that we speculated made it less of a target for anti-aircraft fire. Oh my god, I thought. I am landing in Vietnam!

Long Binh

Long Binh Army Depot was the major Vietnam arrival and departure point for Army personnel and supplies. I was completely unprepared for what met me there. I had fully expected to step off the plane and into knee-high mud where I would remain for twelve months. Imagine my surprise when I found myself in an honest-to-god city, replete with gift shops, snack bars, American television and radio programs, post offices, even laundries. Sure, you walked around on pallets of wood scrounged from under shipping containers to stay out of the mud and, sure, you stayed in barracks that had canvas walls instead of stucco and drywall and, sure, there were new and distinctly different smells and, sure, once in a while, off in the distance you could hear the sound of artillery fire and, sure, choppers shuttled back and forth overhead and, sure, at night you could watch flares dropping and, sure, everyone was wearing jungle fatigues. But it was still a far cry from what I had been led to believe. It was positively civilized!

Long Binh

The shit-burning detail was no doubt contrived to dispel any illusions new arrivals might have about finding themselves in “civilization.” The non-coms in charge took great delight in picking the newest of the new and informing them exactly how they would be passing the time while waiting to be assigned to a unit. They described it as a rite of passage and I suppose it was. I did not escape. My first morning in Vietnam was spent going from outhouse to outhouse, raising the hinged, wooden flap on the rear, dragging out a sawed-in-half fifty gallon drum full of human waste, pouring gasoline into it, and setting it on fire. When it had burned down to cinders, I carefully replaced each drum back under its cargo chute ready for another day’s business. The plumes of greasy, black smoke that rose each morning above every U.S. camp became the routine signs of another day in progress. Since I had no idea how long I was going to be at Long Binh, as soon as I had finished that morning’s job, I set off in search of something to take its place. The second morning in Vietnam, I handed out clean sheets from the supply room, a job considerably more to my liking.

After breakfast and the usual morning details of sweeping the barracks, burning shit, handing out sheets, picking up cigarette butts, etc., all new arrivals had to stand in formation for roll call followed by the reading of assignments. We all listened intently as foreboding names like 101st Airborne, 1st Infantry Division, 1st Air Cavalry, and 4th Signal Group were read off and sighed with deep relief when our names were not mentioned.

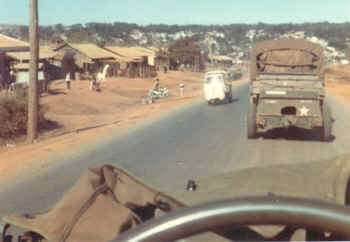

One morning, about the third day, my name came up. I was to be assigned to the 4th PO Group. What in the hell was the 4th PO Group? Post Office was all that came to mind. We were directed to a deuce-and-a-half (Army lingo for a 2 ½ ton truck) for transfer to our unit. As we climbed aboard and settled into the plank seats in the open rear, we discovered we were now members of something called the 4th Psychological Operations Group. How exotic! But my idea of exotic would quickly be stretched beyond anything I could have ever imagined. It started immediately on the drive down the Long Binh highway to Saigon. With one hand on the horn, the other banging loudly on the outside of the door, foot firmly pressing the accelerator to the floor, voice yelling hoarsely, “Get out of the way, you fucking gooks,” and the vehicle seemingly steering itself, our driver easily took us beyond the thrills of any amusement park ride, all the while forcing wide-eyed Vietnamese on foot, bicycle, and motor scooter to leap for the ditches on the side of the road. As if this wasn’t enough, I then came face-to-face with Saigon.

Deuce and a half

Saigon

There are no words to describe my first impression of that city: the sights, the sounds, the people, and, oh yes, the smells. I used to tell friends in a feeble attempt to portray the flat-out assault on my senses, “All my meters redlined at once.” Thirty-seven years later, that is still the most apt description I can think of. At a stroke, my entrance into Saigon was the most foreign, overwhelming, intense experience I had ever had. If someone had taken a picture of me then, I am sure it would have shown a bewildered, gaunt (during the rigors of basic training, I had lost considerable weight), white boy, wearing glasses and jungle fatigues (still showing the creases of first wear), his jaw dropped, his eyes as big as dinner plates, nostrils flared, clearly and completely stunned at the chaos taking place around him.

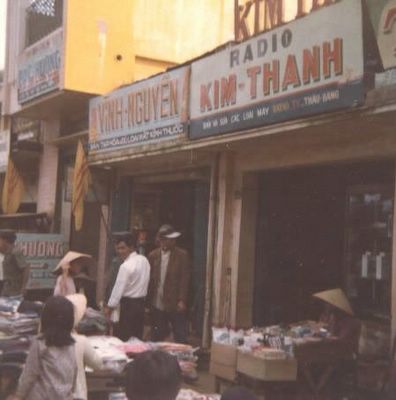

Saigon 1968

A few days later, my level of astonishment reached new heights as I stood at a window in the 4th Psyop Group and watched the comings and goings at a community water tap out on the street. It was mostly women and children, hauling buckets of water back to their homes, doing laundry and dishes, bathing, and washing and preparing food. A woman with a green plastic tub filled with what looked like a large, round, long, pink chunk of meat spilling out over each side arrived at the tap and began carefully washing what was obviously going to be dinner. I watched with some fascination until it slowly dawned on me what I was witnessing. The big, pink piece of meat, the size of a small dog, was nothing other than a skinned rat. Leaping ahead more than three decades in slang and behind three decades in cinema, how fitting it would have been to say, “We certainly aren’t in Kansas any more, Toto!”

My hopes of remaining in Saigon were dashed when I received orders for the 8th Psychological Operations Battalion in Nha Trang. It didn’t matter that Nha Trang was supposed to have a nice beach and to be about as close to a resort area as Vietnam offered. It was “up-country,” a term I quickly learned meant everywhere north of Saigon. The sub-text of course was that Nha Trang was dangerous and could possibly be detrimental to one’s health.

Nha Trang Beach 1968

Nha Trang

Three days of surf, sand, and sun on the South China Sea in Nha Trang, punctuated by touristy strolls around town and souvenir shopping at the PX came to a screeching halt when I found I was to be further assigned to (spoken in a hushed, sympathetic tone), Company B, in (uttered with a quiet gasp in a nearly inaudible voice) Pleiku. Ok, Nha Trang wasn’t entirely paradise. On one of my beach days while advancing my sun exposure from a mere 3rd to a more respectable 2nd degree burn, I narrowly missed being hit by an enemy mortar that landed not more than 100 yards from my beach towel. I took my cue from the other sunbathers and raced to the bunker. No one seemed particularly traumatized and less than twenty minutes later, we were all back on our towels in wartime homage to George Hamilton.

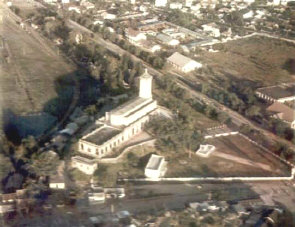

Nha Trang Cathedral

I first met Peter in Nha Trang. Peter was intelligent, funny, loaded with charm and good manners, easy to talk to, interested in me, and a great conversationalist. We hit it off from the start. I was amazed when he told me his job. His entire work in Vietnam consisted of traveling around II Corps (the area consisting of Nha Trang, Pleiku, and the bulk of the Central Highlands), showing Walt Disney movies translated into Vietnamese to children in orphanages. He would usually spend a week or so in each place and since the actual work took up little time, he spent the majority of it doing whatever he wanted. Could this be for real? Had I permanently entered the realm of the absurd? Evidently so. As anyone who has been in the military can attest, even the most seemingly far-fetched accounts like Catch-22 and M.A.S.H. often don’t come close to capturing the bizarre reality. As it happened, Peter was a regular visitor to Pleiku and always stayed in the Psyop barracks. He calmed my jitters with stories of the MACV pool and the nearby steam bath. Knowing I would be seeing him there gave me something to look forward to and I left Nha Trang a bit lighter in spirit.

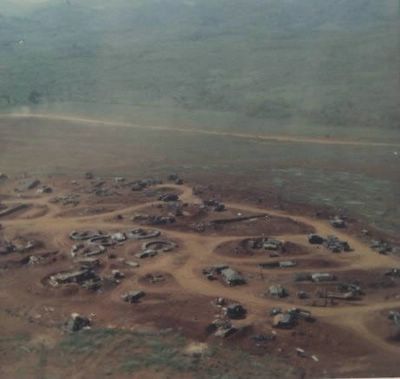

Camp Schmidt, Pleiku and Bien Ho Lake

Welcome to Pleiku

The rain was steady, not heavy, but not a drizzle either. The clouds were low and dark. Moisture hung in the air like a living thing. You could almost hear mold and fungus growing and the smell was thick and fetid. It was getting on toward dusk and I was putting things into my locker after eating a tasteless dinner at a drab little mess hall. I was feeling a million miles away from anything warm and familiar and the weight of the year to come hung on my shoulders. My barracks-mates, still strangers, trooped silently back from dinner and sat glumly on their bunks. Daylight faded but no one made a move to turn on the lights. There were occasional whispers of conversation up and down the row but they slowly drifted away until, except for the constant grumble of the electrical generator across the street, the silence became complete. I sat on my bunk too, watching the others look at their feet with empty gazes. “Hmmm,” I muttered to myself. “This is gonna be worse than I thought.” Suddenly a yell: “THERE GOES ONE!” followed by a loud thud. “YEAH, I SAW THE LITTLE BASTARD!” erupted from elsewhere followed by another thud. The after-dinner ritual, as I discovered, was to sit quietly until complete darkness took hold, wait for the rats to come out, and then try to bash them with 2x4’s as they ran by.

With the rat-bashing portion of the evening’s agenda complete, the lights came on, all types of music began to blare, beer, soda, and hard liquor appeared, care packages and snacks were opened and shared, the dopers adjourned to the back porch, and the pleasant sound of laughter rang out. Welcome to Company B! Never were the words of my deceased hero, Hunter Thompson, more fitting: “When the going gets weird, the weird turn pro.”

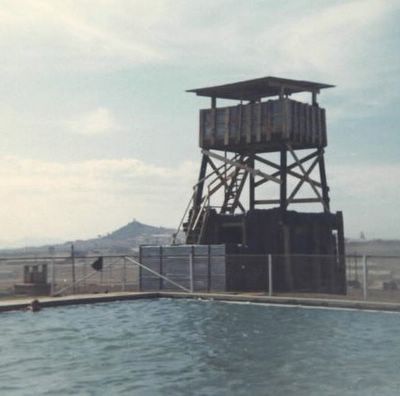

Camp Schmidt, Pleiku (view from guard tower)

Psyops

Yes, weird is one word that described Company B, if not the whole of Psyops, quite well. If I was talking to what my Grandma would call “polite society,” I might say eclectic. Other terms that spring to mind are: assortment, diverse, odd, mixed-up, cut and paste, mis-matched, unique, unusual, distinctive, and just plain peculiar. What else could you call a group of people culled from the entire spectrum of social classes, professions, income levels, and ethnicities who had backgrounds or training in: gathering military intelligence; translating English into not only Vietnamese but also multiple indigenous Central Highlands languages and dialects; designing graphic products for printing, writing copy according to rigid propaganda guidelines; creating and producing radio programming and operating and maintaining a radio station; creating huge varieties of leaflets and brochures and the occasional magazine; operating and maintaining printing presses and equipment; creating flight plans for optimal aerial distribution of leaflets; creating and implementing civic assistance efforts for local villages; training local Vietnamese and Montagnards on civic leadership; building awareness in local Vietnamese and Montagnards of personal health and safety issues; promoting and running a Viet Cong defection program; maintaining an inventory and logistics system for propaganda materials; and a host of other odd little specialties that comprised the strange world of psychological operations? Fortunately, most of them liked to party. There were those who drank, there were those who smoked (dope and/or cigarettes), there were those who drank AND smoked, there were those who whored, there were those who drank AND whored, there were those who drank, smoked, AND whored, and, of course, there was always the odd vice, fetish, or addiction that would jump out of the woodwork from time to time.

Downtown Pleiku

Watching the War

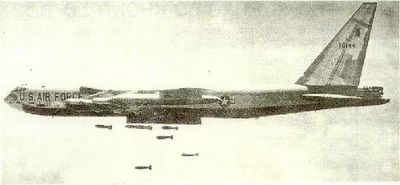

Cookouts at the company area were popular. There was never a shortage of good steaks, chicken, and ribs taken in trade from some mess hall sergeant for our “scrounge du jour.” Beer, hard booze, soda, and cigarettes were cheap and plentiful. The dope was cheap and outstanding. At night, the dopers (I joined their ranks almost right away) would gather on the upper stair landing of the second floor of the barracks, fondly known as the back porch, to get stoned and “watch the war.” For musical background, we had the cacophony of the night insects which, amplified by a nice high, became almost deafening. Our insect orchestra was augmented at regular intervals by the booming of out-going shells fired from Artillery Hill. The light show was provided by flares and tracer rounds. Since special entertainment, by its nature, was never announced in advance, when B-52’s began carpet-bombing on the other side of ridges 30-40 klicks away, the constant muted pounding of the explosions and the faint, ghostly yellow flashes were a source of many “oooh’s” and “ahhhh’s.” Equally impressive and almost hypnotic to watch was the display put on by the so-called “Spooky” gunship. Spooky was a converted two-engine military prop plane with silenced engines and blacked-out running lights, designed to fly over suspected enemy positions without attracting attention. It fired a mini-gun at several thousand rounds a minute. Since every 5th shell was a tracer, the effect was to produce a bright red, laser-like pencil of light that appeared from an inky black sky as if by magic. The pencil would swing this way and that, bathing its target in bullets, all the while emitting a hair-raising “brrrrrrrrrrrap” noise. The Spooky was my personal favorite.

B-52 on a carpet-bombing mission

When we tired of the live entertainment, we would gather at Ted’s bunk and “plug in,” headphones and plenty of grass for all. With Ted as DJ, there was no lack of interesting music. Thanks to Ted and Pleiku, I was exposed for the first time to many of the legends and greats of that era. The Doors, Jimi Hendrix, Janis Joplin, Leonard Cohen, Santana, Judy Collins, Wes Montgomery, Bob Dylan, Jethro Tull, and the Beatles were all staples. Within a week after the Beatles White Album was released, Ted had the full album on tape in his hands as recorded by a friend off of a radio station in Honolulu that had premiered it without interruption. As one of those odd bits of trivia that never seem to float down the mental drain, I remember the station’s ID tag as it was intoned with gravitas by a deep-voiced announcer – “Heavy [slight pause] in Hawaii.”

Pleiku "suburbs"

Work?

My initial job in the company was Operations Clerk. The job description was simple and straightforward: drink coffee; smoke cigarettes; other duties as required. Since there were rarely other duties, I started off my Vietnam tour sitting on my ass most of the day interrupted only by a lengthy noontime break. Lunch usually meant swimming and sun at the MACV pool, zoning out in the steam bath, and burgers at the grill. Peter would materialize every few weeks and hang around for as long as he thought he could push it. The nights were a fine, fuzzy haze of music, “watching the war,” and devouring care packages. Oh, yes, the sirens would regularly announce potential incoming fire IF we were lucky enough to get advance warning. We’d don helmets and flak jackets, often over bare chests and underwear, and stroll out to the bunker in flip-flops, grumbling at being taken away from whatever vice we had been pursuing and wondering how long it was gonna be this time. When a nearby explosion constituted the “warning,” the scene changed only in that the stroll quickened to a brisk jog. I got to be so good at differentiating incoming and outgoing fire that I would awaken instantly from the deepest of sleep at the sound of a Viet Cong mortar being fired 10 klicks away. But, besides occasional guard duty, life was good.

MACV pool

Guard Duty

Guard duty. Arrrrrgh! Picture this: beams of wood, treated with creosote, form the framework of a large cube. Thick plywood is laid across the beams as a makeshift roof. Sandbags are piled at least two deep all around and more on top. There is a narrow entrance. Small rectangles on each side serve as ports for viewing - or shooting. The burlap of the sandbags quickly mildews and rots in the high humidity. Many have split open and are spilling out their contents. The stench is not pleasant. Mingling with the smell of rotten fabric are the smells of rodent excrement and, wafting up from where guards relieve themselves night after night, stale urine. There are two or three unbelievably dirty GI-issue sleeping bags on top. They exude their own strong odor, a thick, muddy, locker-room musk. The bags are there to help stave off the chill that descends on Vietnam’s Central Highlands at night. Two guards are posted on top of each bunker from dusk to dawn. The bunkers aren’t the only guard posts. If the bunkers are Motel 6, the guard towers are the Ritz-Carlton. They have wood floors, chest-high corrugated tin walls and roofs, are high above the smells and vermin, and, compared to the bunkers, offer a night of relative luxury.

Bunker guard post on the perimeter, Camp Schmidt

Psyops is attached to the 45th General Support Group for food and shelter. Since the 45th has first claim, Psyops rarely draws a tower post. When they do, the two Psyops men assigned for that night congratulate themselves on the smile of Lady Luck. The two guards at each post take turns, one sleeping while the other keeps watch, on a schedule negotiated by the guards themselves. Sometimes money changes hands. (“Money” is somewhat of a misnomer. Legal tender consisted of military-issue scrip in the same denominations as U.S. dollars with the exception that paper replaced coins and there were no pennies.) The Sergeant of the Guard makes his rounds every few hours, checking each bunker and tower along the perimeter. A guard at each post must challenge the approaching Sergeant with the traditional, “Who goes there?” and the Sergeant responds with the night’s password. Memories fail and prompting occurs. Both guards sleeping at the same time is not unusual and, if the Sergeant’s preceding checkpoint has not already alerted the sleeping pair by field phone, the Sergeant usually makes enough noise not to be missed.

Work!

Two months had passed when the Company Clerk, never a paragon of serenity under the best of circumstances, suffered a sudden late morning melt-down. With arms waving, tears flowing, and babbling incoherently about morning reports, guard-duty rosters, and rush memos, he demanded a transfer to the Radio Team where, he hoped, chaos could be held at bay and life might resume a semblance of order. First Sergeant E-7 Schneider, a hard-drinking, buzz-cut character right out of Popeye and no fan of men crying, promptly granted the reassignment. He then marched to the Operations office where I was pouring another cup of coffee and announced in a no-nonsense tone, “Come with me. You’re the new Company Clerk.” Say goodbye to the Life of Riley and hello to Radar O’Reilly.

My time with Sergeant Schneider was mercifully brief. His tour was nearly up anyway but the night he showed up at our barracks drunk on his ass, picked a fight, and got the ever-loving shit beat out of him I’m sure speeded things up a bit. His replacement, First Sergeant Shigato Tokifuji, a short, wizened Japanese who positively radiated warmth and a Zen sense of well-being, was just the ticket.

All my mornings started the same. No matter how incredibly stoned I had been the night before, I always jumped on the truck with everyone else and arrived at my desk at 8:30. I would arrange my day’s work in a large pile and, before settling down in front of the “beast” (an Underwood manual), would enjoy a cup of coffee that Toki had thoughtfully made while I was shuffling paper. I often joked that pounding on that damn machine put me in the best shape I had been in since basic training. All day - pound, pound, pound. Every so often, Toki, bless his heart, would look at me across his desk, clear his throat to get my attention, and declare softly, “Stop! You’re working too hard. Here, have one of mine.” He would then shove his pack of cigarettes across the desk and rise to refill my coffee cup. What a guy!

Did I mention that the Company Clerk was exempt from guard duty? I was not only exempt, I drew up the guard duty roster. Gradually, I probed the dimensions of my power and, as in the comics, determined I would use it only for good. The mere act of slowing down on paperwork could mean a delay of orders being cut for someone’s R & R and, of course, the reverse was also true. A phone call to Nha Trang could speedily reward a good attitude with an expedited departure that very afternoon followed by a joyful family reunion in Hawaii the next day. I made it clear that I would not tolerate rudeness or verbal abuse and, given the severity of potential consequences, courtesy generally reigned. Once in a while, some hothead would try to pull the intimidation trick, yelling about writing a Congressman, or, in one instance, making a not-so-veiled threat to kick my ass. It was then that Toki, the Zen master, would beatifically take charge and harmony would reign once more.

Artillery Hill (view from Camp Schmidt)

Donnie Dasher

How to describe Donnie Dasher? You could tell when Dasher was around because there was always somebody nearby smacking his forehead and exclaiming, “I can’t BELIEVE you just did that!” Dasher’s combination of low intelligence, outrageous behavior, and goofy, aw-shucks, ear-to-ear grin made it almost impossible to get mad at the guy but you had to wonder sometimes how he had managed to live as long as he had. Peanuts floating in a beer mug full of whisky? Donnie Dasher. A strain of venereal disease penicillin wouldn’t touch? Donnie Dasher. Putting a rhinoceros beetle on the toilet seat of the shitter at night? Donnie Dasher. I was sitting on my bunk one evening after returning from the regular evening session on the back porch, writing a couple of letters before turning in when I heard the telltale “phooomp.” “This is gonna be a close one,” I thought. An eternal split second of silence followed by a sound eerily akin to bacon sizzling preceded a gigantic explosion. My room was on the second floor street-side of the barracks and, from the shrapnel pattering against the outside of the wall, I knew it was more than just close. Without thinking, I dropped to the floor and began crawling out the door on my hands and knees, joining my fellow human cockroaches swarming down the hall, out the door, down the stairs, and around the corner to the bunker. “Jesus Christ!” “That was mother-fucking CLOSE!” “It was right across the street!” “God DAMN!” “What did it hit?” “I don’t know!” “Shit!” “It was right next to the shitter!” “Holy shit!” “Are we all here?” “Who are we missing?” “Fuck, where’s Dasher?” “He went across the street to the shitter!” “He was in the SHITTER?” “Anybody looking for ME?” Dasher said, laughing as he poked his head in the door of the bunker. “God DAMN! Are you ok?” “You fucker! Were you in the shitter when it hit?” “Sure was,” he chuckled. “Came flyin’ out that door with shit hangin’ off my ass too!” I can still see him standing there, silhouetted in the door, shit-eating grin and all, basking in the attention, regaling the guys with the whole story, and not a detail left to the imagination.

Dropping Leaflets

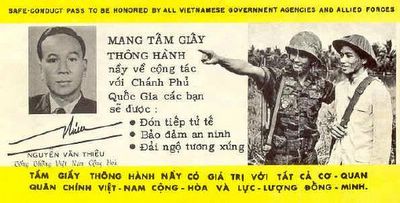

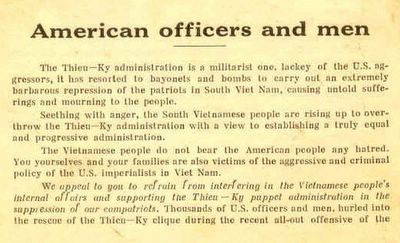

I got wasted on grass pretty much every night for eight months and there were few things that broke the routine. One of them was earning enough hours flying leaflet-drop missions to get my aircraft crewman’s wings. The missions were flown by the Air Force and covered specific patterns over specific targets. The type of leaflet depended on the type of target. “Friendly” villages might receive innocuous information on how to treat water to make it safe to drink or announcements of upcoming Civic Action Team visits. Suspected Viet Cong positions received endless deliveries of the famous “Chieu Hoi” or, as we liked to call them, the “Give Up You Fucking Bastards or We’ll Bomb the Shit Out of You” leaflets. These were literally “free passes” encouraging defection to the South and listing instructions about how and where. Wags in the company insisted that, outside the perimeters of firebases that had been experiencing heavy attacks, the Viet Cong no longer walked on the actual ground but instead trod on a deep carpet of leaflets.

Chieu Hoi leaflet (front)

Chieu Hoi leaflet (back)

With my limited experience and lack of actual crewman training, the aircraft I drew was the O2B, the military version of the civilian Cessna wing-over fuselage SuperSkymaster model, characterized by twin engines in a fore and aft, push-pull configuration. Besides the chute for dropping leaflets, strategically placed in front of the crewman’s seat where the suction could quickly yank stacks of leaflets out of the airplane (also well-placed for disposing of the results of airsickness), the aircraft was also equipped with a tape player (yes, reel-to-reel) and a loudspeaker for broadcasting propaganda messages. The pilot was usually a field grade, desk jockey, Air Force officer, getting in his flying hours.

02B

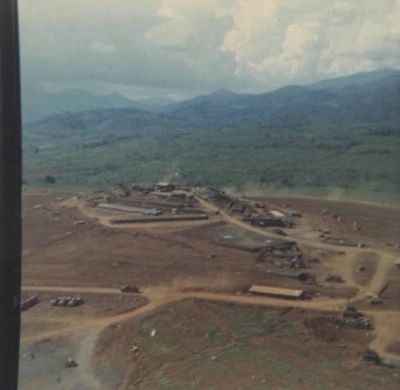

Depending on the mood of the particular pilot, sightseeing tours before, during or after the actual drops or even landing at other airbases like Ban Me Thuot or Kontum for snacks and refreshments might be included in the itinerary. One day as we were barely skimming a dense jungle canopy, in a moment of heart-stopping beauty, the trees suddenly gave way to a huge, grass-covered clearing where a herd of elephants broke and ran for the trees. On Christmas Eve 1968, we toured firebases in the Central Highlands, dropping Christmas card leaflets and playing Christmas music.

Firebase, Central Highlands

The guys ran out of the bunkers that served as their barracks, their bare arms, faces, chests, fatigues and boots the color of the raw and muddy dirt under their feet, waving and yelling, a few in red Santa hats. Merry Christmas everybody! I was headed back to a hot meal after which I would get high and eventually crawl into my cozy bunk where I would tuck the mosquito netting in tight to keep out the rats that occasionally fell from the rafters and drift off to sleep, hoping not to be disturbed by an alert.

Molina

There were a number of guys assigned to Company B we rarely saw. They worked on field teams that covered a large slice of the Central Highlands and they came into Pleiku only occasionally for admin reasons, to rest up for a few days, or to head to or from R & R. Some were assigned to firebases where they would broadcast propaganda by loudspeaker to unseen Vietcong in the jungle outside of the firebase perimeter or when they accompanied armed jungle patrols outside the perimeter. Others worked out of AV trucks that served the dual purpose of mobile Psyop operation and sleeping quarters. Hunting for something different to do one day, I volunteered to drive one of the field team members back to his assigned firebase, Dak To. I picked out one of the better three-quarter ton trucks, dusted off my helmet and flak jacket, scraped the mold off of my rifle, packed some snacks, and headed out. We were supposed to connect with a convoy leaving from Pleiku headed to Kontum and then on to Dak To but we missed its departure by about fifteen minutes. “No sweat,” said Molina, the field guy I was returning. “We can catch ‘em. I know the highway. We’ll haul ass.” Figuring Molina knew what he was talking about, we hit the road. Describing it as a “highway” was perhaps a tad generous. It was a wide, rutted, orange-brown slash of packed earth that, while it was obviously graded on a regular basis (the graders, to my astonishment, were left sitting, unmanned, along the side of the road), clearly showed the punishment it took from the trucks, tanks and other pieces of mobile equipment that passed up and down daily. All vegetation had been cleared up to a hundred yards on either side to prevent a possible ambush but, other than that, we were in the wide open spaces. Being the only vehicle in sight and feeling like we were nothing if not sitting ducks, I got really nervous really fast. Oddly, the cause for my anxiety was that I had suddenly remembered that we had no spare tire and, even if we had, no jack or tire iron to change it with. Molina, obviously immune to such trivial nonsense, rolled a joint, lit it, and took an enormous hit. “Hey, man,” he said, straining to talk while holding the smoke deep in his lungs. “Let’s enjoy the r-i-i-i-i-d-e!” He was right. I had soon forgotten about everything but the rush of the wind in my hair, the jungle flashing by on either side, the roar of the engine, and the thrill of piloting the truck over challenging terrain, not even minding that we didn’t manage to catch up with the convoy until Kontum.

Firebase, Central Highlands

I had driven to the company area to pick up outgoing mail and had come back to the barracks before heading to the post office. It was a Saturday and I was moving slow. I wandered around the barracks for a while, chatting with the guys, idly passing the time. I had stopped by my room for something or another when Molina, in from the firebase for a few days, stuck his head around the corner. Originally from Guatemala, Arturo Cesar Molina was short and wiry with a big shock of coal-black hair combed back from his forehead in a glistening wave. His fatigues, firebase dirt brown, were tailored and pegged in the non-regulation style that everyone knew meant, “I’m from the FIELD, mother-fucker, so don’t FUCK with me!” His dark, ever-present sunglasses conveyed yet another message: “I’m stoned.” “Wanna go smoke this number with me?” he leered, holding up a joint. “Sure,” I said. “Why not.” I didn’t know Molina very well but my impression of him was vivid. He seemed somehow to radiate evil, a palpable “badness.” Two puffs later, on the back porch, I found myself getting high with an astonishing rapidity, higher, in fact, than I had ever been before, scarily high, and it wasn’t slowing down. “Holy Christ!” I gasped as I turned to Molina. “What IS this shit?” “It’s an opium-dipped ‘j,’ m-a-a-n,” he said, laughing demonically. I was going up like I was strapped to a rocket. “You fucker,” I said. “I’m fucking WORKING! I can’t work like THIS!” “Sure you can, man. I do it A-A-L-L the time,” he said, tossing his head with crazed laughter. I stumbled out of the barracks to the truck. Somehow I managed to get it started and into gear. I was hallucinating badly. Negotiating the turn at the corner, I watched as my hands rotated the steering wheel to the left, became detached from my wrists and flew out the window. Faintly, the sound of the engine revving to dangerously high rpm’s penetrated my consciousness and I struggled to convince my foot to depress the clutch and and my hand to shift gear. As I stood in line at the post office with the other mail clerks, I was certain my eyes were melting and running down the front of my fatigue jacket. I pulled into the parking lot in front of my office in the company area, turned off the engine, and slumped over the wheel. Peter pulled the door open and helped me out. “What the hell happened to YOU?” he asked. “You look like hell.” “Somebody slipped me a Mickey,” I said. The hallucinating had stopped, thank god, only to be replaced by the mother of all headaches. Peter, bless his heart, finished up the mail chores for me and then took me over to the MACV pool where he pushed me in, clothes and all. After dragging me out, he led me like a little kid over to the steam bath where he helped me out of my clothes and proceeded to literally steam the shit out of me.

Perks of Power

Occasionally, brass would visit from Group headquarters in Saigon. They would typically arrive at Pleiku Air Base in the morning on the first flight and check in with me after being picked up and driven to the company area. More often than not, the first thing they did was inquire about any recent or expected attacks while they looked anxiously around, no doubt expecting a mortar to explode over their heads at any moment. If I had suddenly jumped up and screamed “BOOM!” at the top of my voice, I’m sure there would have been at least a few that would have gone into cardiac arrest. I was, however, regulation polite and deferential, standing and saluting, saying “Good morning, Sir, welcome to Company B,” blah, blah, etc. Ah, but power corrupts and, being a mere mortal, I couldn’t resist. The degree to which those courtesies were reciprocated, unbeknownst to the officer in question, would determine to a large extent the quality of said officer’s return trip because, you see, the second thing to issue from said officer’s mouth was most often a request for me to schedule his return flight for that very afternoon. God forbid they should have to spend a night in

C7A Caribou

R & R

I spent my R & R in Hawaii. I had any number of choices ranging from Bangkok to Sydney to Singapore to Hong Kong to Taipei. But, again, being the good boy, I paid for my mother and brother to fly to Honolulu where family friends who used to be next-door neighbors back in Colorado had warmly offered their home. Short as it was, R & R remains somewhat of a blur - except for two things.

I had only experienced blind rage once before. When I was about ten or eleven years old, I played quite a bit with two friends, David and Scott, fraternal twins from up the street. For the most part we enjoyed each other’s company. David tended to be somewhat of a bully and, no doubt sensing my vulnerability, would sometimes amuse himself by picking on me. He was going at it full tilt one afternoon in the side yard of my house when, suddenly, I snapped. I was all over him, blazing with anger, shaking him, screaming for him to knock it the hell off, that I’d had it, no more, etc. I know I scared him badly because I could see it in his eyes. “Whoa, take it easy!” he said as Scott pulled me away. But as much as I had scared David, I had scared myself even more. Erupting like a volcano was new to me and I was frightened. So, after flying many thousands of miles, there I was in Hawaii, fresh from the war, watching people go about their daily lives, doing errands, going shopping, driving to work, spending time with their families, when, without warning, I became choked to speechlessness with rage. “LOOK at them!” I thought. “They’re acting as if everything is just fine! It’s NOT fine! Don’t they KNOW what’s going on? How DARE they?” The sheer power of the anger was staggering and I had no idea what to do with it. So I did what I always did with my bad stuff. I sucked it up and buried it with everything else somewhere deep inside.

The second thing I clearly remember, I laughed off at the time. We were all sitting around in the living room, talking. I was watching TV, catching up on the new shows in the current season. Our friends had a very nice, typical-to-Hawaii, semi open-air house across the pass from Honolulu, not far from the beach. They were lovely people, hospitable to a fault. Their cat, Piawaquet, that I remembered from Colorado had been sitting on top of the television, surveying his domain. Something must have startled him because he suddenly leaped down sending a heavy vase crashing to the floor with an audible thump. Without thinking, I dropped to a prone position on the carpet between the coffee table and the sofa. When I looked up sheepishly, all eyes were on me. They had no clue about what to say so, ever the care-taker, I chuckled as I got up. “Yeah, well, remember I told you we had been getting some mortar attacks last week. No problem. It’s just a habit.” Ha, ha.

Leaflet "they" dropped on "us"

Moving Downstairs

When I returned to Pleiku from Hawaii, I impulsively packed my things and moved downstairs to the dead zone of the barracks, the party-free area where the readers and those who just wanted some peace and quiet congregated. After once again experiencing in Hawaii what it felt like not to be stoned out of my mind every single night, I had a need to put distance between me and the nightly getting-high sessions. Something had changed but I didn’t know exactly what. I only knew this was something I needed to do. At first, my former party-mates grilled me thoroughly. Was I mad at them? Had they done something wrong? No and no. For a while, every evening one or two of them would stop by to announce that “We’re out on the back porch if you wanna join us.” Eventually, to my relief, they figured out I was serious and left me alone.

Extending

What prompted me to make the decision to extend my tour? Clearly, no one in their right mind could possibly want to spend another six months in Vietnam. Well, it wasn’t as crazy as it sounded. I figured that, with more than a year and a half left of a three-year enlistment, doing my remaining time in the Stateside Army after the relatively lax atmosphere in Vietnam would be hell. Sticking around in Pleiku, however, seemed too much like courting a death wish. But all was not lost.

Peter of the incredibly cushy job had inevitably pushed things too far. He had had his knuckles rapped and was subsequently relegated to office duty in Saigon. Interestingly, it hardly qualified as punishment. As one of two assistants to the Chief Chaplain Advisor to Vietnamese Chaplains, he had almost as much free time as he did previously with the added bonus of being able to check out all the good Saigon restaurants and take advantage of all the other pleasures Saigon had to offer. Listening to me talk about my dread of returning to an assignment in the States, Peter offered a suggestion. His tour in Vietnam was almost over as was his time in the Army. His colleague, the second assistant (they needed only one), was going home at the same time. If I put in my application to extend and specified I wanted that job, Peter would work the angle from the other end. “Wow,” I thought, “living in a hotel, eating out, soft job! What’s not to like?” It would buy me an extra six months of freedom from the mind-numbing, infuriating rigidity of the Stateside Army and give me a nifty new experience to boot. With Toki constantly repeating in my ear, “Don’t do it,” I commenced to jump through the hoops.

25-cent MPC (Military Payment Certificate) - used in lieu of actual currency in Vietnam

Good ol’ Toki! He really turned up the heat on me. He was convinced I was making a terrible mistake and pulled out all the stops to keep me from going through with it. “Now, stop and think for a minute,” he would say. “Can’t you see it? You are driving in your car, your OWN car, your very own NEW car! You see an ice cream stand. You stop and order a big, thick milkshake. Chocolate. With whipped cream on top. Mmmmmmm! Think how good it’s going to taste. You can’t get a milkshake in Saigon.” “Oh, c’mon, Toki,” I would say. “Stop trying to get me to change my mind.” But nothing was going to stop him. “Wait! Look! There’s your mother. The bell rings. She’s walking to the door. She opens it. Two men in uniform are standing on the front porch. Oh, no! NO! NO!! It just CAN’T be! Not my son!” Three whole weeks I had to put up with that before the paperwork was all signed off. But hey! Ya know what? He may have been right.

Saying Goodbye

My last night in Pleiku happened to be Toki’s as well. He knew how much I liked to drive the deuce-and-a-half so he arranged for me to drive him and a few others to the Pleiku Air Base NCO Club where he was buying. Many beers were consumed. Many, many, many. Raucous laughter was the order of the night. As we were preparing to leave, through a blurred haze I saw Toki gathering up empty bottles and stowing them inside his fatigues. He must have had several dozen, crammed in the big pockets of his jacket and pants, clutched under his arms and against his chest. “What the hell are you doing?” I asked. He smiled his Buddha smile and headed for the door. Given my advanced state of intoxication, I was working hard to stay on the road while making sure to shift gears before the engine wound out to dangerous rpm levels when I oh-so-slowly became aware that Toki, riding shotgun, had the right-side door open and was standing on the running board. His beer bottles were stockpiled on the seat and, swinging back and forth, holding on to the the door handle with one hand, he hurled bottle after bottle against the walls of the military wood-frame buildings as we passed. Catching me looking at him open-mouthed, an evil grin spread across his karate master face. “Now, see!" he said. "Isn’t this fun?”

Pleiku Air Base 1969

Nothing would do after dropping Toki at the NCO barracks but a joyride. I sped directly to the broad, open, rutted parking area next to the PX, an area, I thought, perfectly suited to spinning doughnuts, never mind that the vehicle in question was a quad rear wheel, six-gear diesel truck. In a master stroke of stupidity, I neglected to remember that the parking area was located directly between the PX and the MP station. With only one doughnut to my credit, an MP appeared, looking vastly amused, and why not? It was probably the only time in his career that he was able to get up from his desk, go outside, and apprehend a driver for a moving violation – on FOOT! My friends and I found ourselves seated in front of the MP’s desk, thoroughly abashed and shit-faced drunk. “I’m going to have to call your First Sergeant,” he said. “We’ll see what he says about this. What’s his number?” Thoughts raced through my head as I spouted the requested digits. It took Toki a long time to answer and, for a minute, I thought he wasn’t going to. When the officer explained the situation and stopped to listen to the response, he held his face blank. “Good night, First Sergeant,” he said, putting the phone back in its cradle. He looked at us, still expressionless. “Ok, you can go,” he said. “But it better be straight back to your barracks.”

The next day’s hangover was monumental. My head felt as big as Kansas, my stomach was considering relocating somewhere outside of my body, cotton filled my mouth, and I was unsteady on my feet. Toki looked as bad or worse. As I have gained in years if not wisdom, I have come to realize that my karma is never more than a few paces behind me. Toki and I laughed, painfully but genuinely, recalling the night before as we were driven out to the 4th Infantry Division airstrip at Hensel Field for the flight to Nha Trang. Waiting for us in all its glory was none other than a C7A Caribou. “It’s not too late to change your mind about Saigon,” Toki said, nudging me as we climbed on board, lugging our gear.

SAIGON

My boss, the Chief Chaplain Advisor, an ordained Methodist minister, was a jerk, something I can now say with authority. But back then, my first tendency when things didn’t go well was to blame myself. Perhaps once or twice a week, the Major would make an early morning cameo appearance in the office. The rest of the time I had little idea either where he was or what he was up to. I later learned that he was very active in the black market in U.S. currency so no doubt he was up to plenty.

At the time, I was not only on my own; I was also very much alone. The office was in a Vietnamese military compound, 33 Hai Ba Truong St. There was only one other American who maintained an office there and I think he showed his face a grand total of three times the entire time. In effect, I was not only the only American but also the only English speaker there all day. The Major rarely gave me anything to do but, with crystal clarity, he made quite sure I understood my principal responsibility was to “man the office.” This I correctly interpreted as answering the phone so that when the head shed called, appearances would be preserved. Sometimes he would leave me the jeep so I could make the rounds of the Vietnamese Chaplain Directorates, picking up and dropping off various pieces of paperwork that had made their way through the myriad channels of two vastly different systems. Loneliness descended like a pall.

The Press

Let me digress for a moment. In the acknowledgements, I mentioned my senior year high school religion teacher. Saigon was where the seeds he planted began to push their green shoots above the soil. Each afternoon, upon leaving work, I would walk from the office to the bus stop on the way back to my hotel. My route took me past the veranda of the Continental Palace Hotel, an open-air bar complete with potted palms, rattan furniture, and ceiling fans turning lazy circles, the very bar used as a setting by Graham Greene who spent long hours writing there over gin and tonics. As I passed the whitewashed balustrade, various snatches of conversation in English would drift my way. The same group of men was often present at the same time each afternoon. Eventually, as I pieced things together, I learned that they were the news team from Time magazine presided over by Time’s then-Saigon bureau chief, Marsh Clark, not an unfamiliar name to me.

Continental Palace Hotel

As a budding news junkie, I had already been reading Time magazine for years. Staying informed in Vietnam presented a difficult challenge since I was generally restricted to the military daily paper, The Stars and Stripes, and the news broadcasts of AFVN, the Armed Forces Vietnam Network that was memorialized in the movie, Good Morning, Vietnam. When I could, I read Time’s international edition, a rare commodity in the Pleiku PX but often available in Saigon. I had formed my perspective of Vietnam well before arriving there, largely based on Time’s reportage, thus one of the reasons for my initial astonishment at experiencing the vast difference between that perspective and the reality of being on the ground.

Time’s coverage, even then not substantially different from how today’s media cover any significant event, tended toward the “big” stories, a euphemism for news that would attract the most readers. For a news crew in Vietnam that meant an early morning check-in with the various unit public relations officers often followed by a chopper ride to firebases where nasty firefights had occurred the night before. Anybody associated with the news business knows how it goes. Zip, zip. Get some good pictures, maybe an interview or two, stroke the officer in charge, tsk-tsk, wish ‘em all good luck, get back on the chopper for the ride home, whack out some lines in the bureau office, phone it in, and head for cocktail hour, leaving the staffers to pick up the loose ends. But readers like me ended up forming their entire view of what was happening based on accounts of bullets flying, close air support from jet fighters, artillery shells exploding, human wave attacks overrunning concertina-wired perimeters, body counts, and blood-spattered U.S. troops being medevac’d to field hospitals from jungle clearings. It was impossible to know that those occurrences, although certainly tragic and newsworthy, were often isolated instances in a fairly large swath of real estate where a great deal more legitimate news took place unreported every day.

While my Vietnam included that particular slice of reality, it was also considerably larger and, the more I read what I and the rest of the world assumed was comprehensive reporting, the more frustrated I became. Why didn’t they wake up and look around? I could show them a lot of news they were missing like, for instance, the time I accompanied local workers from the Vietnamese Catholic Chaplain Directorate with two flatbed trucks to Long Binh Army Depot to collect damaged and scrap material to use in a church construction project which, once we returned to Saigon, was promptly driven to the Cholon district and sold for ready cash. Or, how about the CIA agent who sometimes stopped by the barracks in Pleiku for a few beers? “So, what is it exactly that you DO?” we naively asked. “Ice picks and cotton balls,” was his enigmatic reply. Many beers later he volunteered that his job was to “neutralize” the Viet Cong infrastructure. How he went about that was, based on intelligence gathered over days and weeks, to sneak into a village late at night, creep into a suspected Viet Cong leader’s hut while he was sleeping, plunge an ice pick into his brain through the ear, dab up the resulting small amount of blood with a cotton ball, and quietly leave. In the morning, the body would be discovered and the cause of death would be unknown. How about the Montagnard plan, code-named FULRO, to overthrow the South Vietnamese government in the Central Highlands? How about the black market and American’s who were amassing small fortunes in currency swaps and getting it to bank accounts in Switzerland? But, to my increasing anger, what I would overhear Marsh and his buddies talk about was an air-conditioner that wasn’t working at the Ritz (the correspondent’s hotel), where they were going for dinner that night, how much they had had to drink the night before, how they disliked having to get early up in the morning, or how rough the chopper ride was. Ok, they were human too, just like the rest of us. But it didn’t seem right then and it still doesn’t. I have never viewed the news media in quite the way same since. One of my many de-flowerings, I guess you could say.

Monument in central Saigon

Gloom

My vision of a cosmopolitan experience, rich nightlife, a cool, almost diplomatic level job that didn’t demand too much, and a fascinating new city to explore collapsed under the weight of loneliness followed by what I now see as a deep depression. It started with physical symptoms: constriction in the sinuses, a post-nasal drip that wouldn’t go away, pain in my neck when I would turn my head, upset stomach, and what felt like swollen glands in my throat. There was a military clinic directly across the side street from the hotel. Numerous visits later, I came away with the same diagnosis I was given on the first visit – nothing wrong. “C’mon, doc,” I thought to myself. “I KNOW something’s wrong. Why can’t you figure out what it is?”

Day after day, I would sit in the office, reading and staring out into space. As was now my habit, at 8:30 I was at my desk. At 11:30, I headed back to the hotel mess hall for lunch and then to my room for more reading and a nap. Back in the office at 2:30, I’d then retrace my steps to the hotel at 4:30, read some more and go downstairs to dinner at 5:30. Sometimes on evenings and weekends, I would take long walks, exploring various parts of the city. Cholon, the Chinese quarter, was where the big military PX was located and it always warranted a trip. I visited the zoo which actually wasn’t in bad shape, all things considered. I stood outside the Presidential Palace, hoping to see Thieu and speculated on what went on inside. I watched helicopters fill the sky during Nixon’s visit and, later, McNamara’s. Once in a while, I’d pay a visit to the enlisted men’s bar, grill, and nightclub atop the Palace Hotel. More often, I would drop by the bar at the American Embassy which featured (imagine, right there in Vietnam!) ice-cold Heineken - on TAP! (I’ve since learned that correspondents, contractors, diplomats, and other foreign mission personnel never, ever forego their accustomed standard of living. Live like the locals? War zone? Please.)

A Saigon hotel used by U.S. military (not U.S. diplomats)

Two Taiwanese Army colonels occupied the office next door. They must have taken note of my plight and began to invite me over for morning tea. They were very nice guys and the tea, my first exposure to genuine jasmine, was wonderful and the smell intoxicating. They took me out for dinner a couple of times to their favorite Chinese restaurant where I experienced oriental hospitality at full throttle – a table groaning under the weight of a dozen courses and two pairs of eyes making sure that I ate until I could not manage another bite, all the while keeping the waiter on the move replacing every empty dish with a full one and making sure the beer in my glass was never more than a few centimeters from the top.

Back Up-country

I truly do not know what I would have done from that point had not my fortune taken a rapid and unanticipated turn. My Chaplain, the jerk, reported in through the operations directorate of the U.S. MACV Command. This reporting relationship paralleled the Vietnamese structure which considered chaplaincies part of operating units. (In the U.S. command, the Chaplain Corps has its own separate structure. There was another largely irrelevant difference. The Vietnamese Chaplain Directorates were organized by religion - Buddhist, Catholic, and Protestant. The U.S. Chaplain Corps is organized by service - Army, Navy, Air Force, and Marines.) The MACV Command Chaplain, somewhat of a martinet, was unable to get over the fact that there was a U.S. Chaplain in the MACV structure that didn’t report to him and was constantly trying to get my Chaplain to agree to take steps to move under the Command Chaplain’s structure. (I’ve learned over the years that these are the REAL battles. Everything else is footnote.) My Chaplain, for good reason as I came to later learn, was very resistant to the possibility of having someone watching over him that might want him to account for his time and/or whereabouts. Meanwhile, in Washington, D.C., the political wheels continued to turn.

MACV Headquarters

It was a mere two and a half months after I started in Saigon that the first U.S. troop cuts were announced. The Command Chaplain pounced. Summoning all of his full-bird colonel huffery and puffery, he marched over to the Operations Directorate where he suggested that they remove the chaplain assistant position from the Chaplain Advisor’s TO & E (Table of Organization, Manpower, and Equipment). The head of the Operations Directorate, himself a full bull, was delighted. He could now earn untold brownie points by demonstrating his willingness to support the troop cut directive by offering up the very first sacrificial lamb – ME! The consequence for my boss was that he was then forced to obtain his administrative support from the Command Chaplain’s office, making reporting to the Command Chaplain a moot point. “Sorry,” I was told. “You’re going to Danang.” Somewhere, I just knew Toki was smiling to himself and saying, “See. I told you not to do it.”

“DANANG! Oh, no,” I thought. “The MARINES are there! THAT’S where lots of people DIE! Can’t I please stay in Saigon? PLEASE? Anywhere but Danang.” I wrote my Congressman, citing the signed agreement under which I had extended my tour. My mother got in the act. I wailed. I complained. I begged. It was no use. With a terror-stricken heart, I boarded the C-47 at Tan Son Nhut, bound for Danang.

DANANG

Without a doubt, Danang was one of the most beautiful places I had ever seen. After reporting in at MACV Advisory Team I, I was at once assigned to be the second of two chaplain assistants to the I Corps Chaplain, a pleasant, funny, and caring Anglican priest right out of the pages of an Agatha Christie novel, complete with pipe. The Marines, I was told, never send out even a two-man patrol without a public relations guy in tow; one of the reasons, I was assured, why “Dateline: Danang” had etched itself into my consciousness and my impression of Danang was so off the mark. China Beach was a marvel.

China Beach, Danang

Danang Bay was enormous and surrounded by beautiful mountains. Monkey Mountain, at the end of the China Beach peninsula where the river joined the bay, stood magnificent guard over a place to rival any setting anywhere in the world. My quarters, a former hotel, was in a residential district slightly to the south of downtown. Across the street and down a half-block, the Chapel was white-washed clapboard with a lawn and a free-standing bell tower in front. It might have been transported directly from the English countryside or possibly a movie set, so cozy and inviting did it appear. The other chaplain assistant and I quickly became fast friends. Duc, the Vietnamese woman who cleaned the chapel, was a delight. All of us were always teasing and joking. Duc’s husband was off somewhere serving in the South Vietnamese Army and she and her four children lived a few blocks away with her parents. Every other Sunday afternoon, after the morning round of services, we were all invited to dinner at her folks’ where the men sat around the table and the women shuffled to and fro with dishes of food or shyly peeked around the corners of doorways with children clinging to their skirts. The nightmare of Saigon ebbed away like a bad dream. Well, not quite.

Why are we here?

Permit me another digression. A majority of Americans who served in Vietnam rarely had the chance to talk to Vietnamese other than the ones who cleaned and did laundry and certainly didn’t get to know them and their families personally. In this way, I was most fortunate. Since Duc and her family were the first Vietnamese I got to know beyond the formal, business stage, I had a million questions. Was it hard for Duc to manage with her husband gone? Did she know where he was? Did he get to come home occasionally? How long had he been gone? What were they going to do when he got back? Would she continue to work? What did her father do for a living? What were her kids like? Did they go to school? And, of course, what did she think of the war? What did she think of North Vietnam? What did she think of the Viet Cong? What did she think of the South Vietnamese government? What did she think of democracy? What did she think of communism? What did she think of Americans? After she decided that there wasn’t much she could say to upset me or cause a big reaction, she spilled the beans. She didn’t know where her husband was; only that he was off fighting somewhere. She rarely heard from him and he never got to come home. He had been gone for over three years. For all she knew, he might even be dead. She loved her kids and couldn’t imagine life without them. She loved her parents. She not only worked at the chapel, she took in laundry on the side. Her father worked for a construction firm run by South Koreans. She thought the South Vietnamese government was full of crooks. She thought the Viet Cong were thugs. She thought the North Vietnamese were snobs. She thought most of the Americans she had met were pretty nice people although she had met some assholes (my words, not hers). She didn’t give a hoot for democracy. She gave even less of a hoot for communism. She had never lived when there wasn’t a war going on but she hated it and couldn’t wait until it was over. All she wanted was to have her husband come home so they could raise their kids together, put food on the table and have a decent roof over their heads. Right there, in one short conversation, my world view changed forever. “Isn’t that what we ALL want?” I thought. “If that’s what it’s all about,” and instantly on listening to her, I intuitively knew that she spoke a universal truth, “what in the hell are we doing here?”

Main street near hotel

Fear, Anxiety, Bob Hope and Adios

Deep down inside, I remained frightened, very frightened. I managed, finally, to screw up the courage to call the medical clinic at China Beach and request an appointment with the chief psychiatrist. Fortunately, I didn’t have to disclose a reason and nobody tried to put me off. If there was a real-life role-model for Sydney, the shrink in M.A.S.H., this guy would have been it. His looks, his mannerisms, everything was the same. Maybe that’s only my romanticized memory but I remember when I first saw the character appear on M.A.S.H., I almost fell off my chair. “So, what’s the problem?” he asked, gently but direct and to the point. I told him straight out, surprising myself. I don’t think he said “Hmmmm” or stroked his chin but he may well have. Honestly, directly, compassionately, he looked at me and said he could understand how that might be causing me some problems with anxiety. Then, equally matter-of-factly, he proceeded to say that helping me was out of the question. His voice took on a heavy, intimate, and deeply weary tone. “Do you know what triage is?” he asked. I nodded. “Well,” he continued, “there are situations I have no choice but to pay attention to. When a grunt on a firebase decides he can’t take it any more and shoots himself in the foot so he can go home, when a marine hates his first lieutenant so much that he tosses a hand grenade into his tent, when things like that come to me, I’m the first line of response. I’m the only psychiatrist in I Corps. Just me. That’s it. I wish I could help you. I really do. But I’m afraid you’re going to have to wait until you get back to the States and find somebody there.” To this day, recounting that story never fails to stir deep feelings, not so much for me, but for the doc. At that particular moment, with me, with what I had just revealed to him, with what he was dealing with himself, I am sure no one could have handled it better. My hat remains off to him, wherever he may be.

Han River, Danang

But where did it leave me? Nowhere, of course, the same place I had been for a long time. As the clock ticked down to my final departure from Vietnam, I began to have a recurring dream. I was in an airplane on my way back to the States. I was sitting in a window seat. We were somewhere high over the ocean. As I looked out the window, I could see that the plane was flying erratically, gaining and losing altitude, turning left and then right, but gradually sinking lower and lower until it was almost skimming the wavetops. In one of those odd scenes that crop up in dreams, the plane was also zigging in and out among military vessels as it tried to make its way through them and back to open water. Somehow I knew we were going to ditch. That was it. Night after night, always the same.

Bob Hope brought his show to Danang that Christmas. Bob Hope had always been one of my mother’s favorite entertainers and I had spent many years watching all his shows with her in front of the TV. I liked his sense of humor too and was all cranked up to go. “Here,” I thought, “is the perfect end to my Vietnam experience, seeing the Bob Hope Christmas show, live, in Vietnam.” Well, guess again. After the brass had skimmed theirs and the combat guys from the field who were being brought in special got theirs and the Marines who always got the pick of everything got theirs, there wasn’t a single ticket left for two poor chaplain assistants. And, to make matters worse, I had to listen to it on the radio.

Supposedly, as a Vietnam returnee, you had your pick of posts in the States. I briefly considered requesting the post adjacent to my home town in Colorado but just as quickly rejected the idea. My time in high school was full of derision for the Army “doggies” as we called them who would cruise up and down the main drag at night and on weekends, drinking beer, and being generally obnoxious. I couldn’t feature being a doggie in my home town so I requested a post in the Missouri Ozarks, not terribly far away. Besides, so went my reasoning, I had lived in Missouri before.

12 Comments:

I read all of it. I am trying to figure out what the attraction to war is.

ever heard of irony...?

comments collected from kos:

"I just sat here and read the whole thing. Absolutely riviting! Wonderful pictures. My dad was in Vietnam too. He was about 44 when he went for the State Dept. Was there for six months, returned and never said one word. I have absolutely no idea what he did there. I doubt that he joined the troops at his age. He died in his sleep about six months after his return. Corner could not find the cause of death because he had absolutely nothing wrong with him other than the fact that he died." - elveta

"Never were truer words spoken. Thank you." - tiggers thotful spot

"Awesome. Great writing. Thank you for sharing all of that with the world. Since I'm not quite old enough to remember Vietnam, it's good to hear what it was really like, instead of a Hollywoodized version of it." - Toastman

Thanks for that, I felt like I was there (although some of those pics sure look like eastern Colorado!)

Have you ever thought about writing a book about your experiences there?

Oh, by the way, do you ever keep in contact with any of the guys you knew there?

Came accross your article by searching for any info on my time in Pleiku at 8th psyop Bn, company B from May 1968 to 1969. I spent most of my time with the night shift in the print shop and slept during the days. But I do remember some of the guys that you mentioned. I have plenty of pictures since I was able to use the photo van while we were working to develop my photos. Your article brought back many memories of those days and I am sending it to my daughter to read because she is interested in what I did in those times. In reading that article I could not have expressed anything better or more thoroughly than those words you used, and remembering the details. Thanks a lot. If you have a list of names that you remember, I would be interested in getting a copy since I am bad at remembering names.

John Shady

jjshady@comcast.net

Came across your site - fabulous. I was at Camp Schmidt the same time as you - I was a finance clerk there for 13 months. It was so cool to see the pictures of Pleiku and the Camp after these many, many years. The description of the guard towers is so vivid for me. Thanks for the trip down memory lane and don't forget, hubba-hubba GI.

B Berger

Enjoyed your article. Excellant read. I was at Camp Schmidt from 12/66 to 08/67 with the 243rd Field Service Co. I was always told there where 5-7 support troops for each combat soldier. Over the years I've met very few support people.

You've painted a truer picture of the War than I've ever heard.

Best regards,

Len

lparkin@juno.com

Hey I googled my Grandpa's name and it came up in this Article that you wrote. I am Pleased to tel you that I am very Grateful for what you have said about him. Yes my Grandpa Shigato Tokifuji was a real soldier and he loved his country very much. I know that he was very proud of what he did, He did not consider himself a Japanese-American he would say I am 100% American.

I knew 1st Sgt Tokifugi. Served with him at Ft. Bragg in 65 then we shipped together to Nam on January 66 on the USNS Pope. 1st Sgt was sent to Nha Trang with the 245th PSYOPS Company where he was the top Sergeant. I went to Saigon with the HHC 6th PSYOPS Ban. After a couple of months with HHC I asked for a transfer and was sent to the 245th in Nha Trang. When I arrived Sgt Tokifugi received me and David Luke with open arms. I knew Tokifugi was a good man, great guy. He told David and me not to unpack because we were going to the detachment in Pleiku. I thought hot-diggity-dam, Pleiku where I wanted to be. I had friends in PSYOPS all over Nam. Some were sent to the Marines and others spread out thorugh the other Corps Regions. In Pleiku I had several friends. Before leaving Nha Trang, however, Top (Tokifugi) asked David and I if we had bathing suits. No we said but we ahve shorts. Top said, "Great" there is nothing for you to do here so take a 3/4 ton truck and go tothe beach. David and I jumped on a 3 quarter ton but before we left, Top said, "Wait a minute, do me a favor while you are at the beach." "Waht's that Top?" I have some empthy sand bags over here that I want you to take and birng back full." Yeah, right, go to the beach. Well David and I loaded up the sand bags onto the 3 quarter ton. When we got to the beach we went in the water for a while and then started filling up sand bags. We had a oodles of emptry sand bags. When we had enough sand bags filled with sand, we decided to fill even more bags until the truck look like it was goign to break an axle. We drove very slowly back to Top's tent and when we got there I honked the beep beep horn that the truck had. All Top coul dbe heard yelling no tto honk the horn anymore. I yelled, "Top, come out here so you can see the sand bags". When Top came out and saw the trcuk loaded down almost to the ground he yelled at us, unload it, now!! He laughed about that many months later. Great guy!!

I just read your article and was at Co B PSYOP at Camp Schmidt from Jan 1969 till March 1970. I provided power to the radio station transmission tower on the hill outside of Pleiku.Love to here from some of the guys there @ that time. I believr Toki was there when I first arrived. I was known asPFC because I was te only PFC in the group as all were SP-4 or SP-5 with the PSyops group. Funny you mentioned the round that almost hit the shitter. I can"t remember exactly when it happened to me but I was in the shower and a round landed just past the church behind the shitter and all the fire and shrapnel went over my head and knocked my butt out of the shower and I ended up in the bunker with nothing but soap suds on and beat ass to barracks after a couple minutes. Don"t know if same time or just a repeat. Love to hear from some guys that see this and remember samr time. I am RHUGs@msn.com

I'm on Memory Lane

Googled Sgt Tokifugi and came across your article. Great reading!!

Arrived at Pleiku Psy Ops, New Years day 1966. I transferred with Sgt Tokifugi to Nha Trang.

Pictures of him

https://picasaweb.google.com/108361885725204278481/196625thPSYOpsOffice#5370754012032954434

https://picasaweb.google.com/108361885725204278481/196625thPSYOpsOffice#5370754039926693762

Man I have to say your recollection of camp Schmit was spot on. I was at Camp Holloway before Camp Schmidt. Our outfit ran the Ammo dumps at Holloway and in the sticks beyond artillary hill. We also had detachments at Kon Tum and dak To. We were on the west side of the camp and pulled many a night on guard duty. Running convoys to Kon Tum and To Batt. 125 miles west. Thanks for the memories brother Many a night in the enlisted mans club drinking 25 cent beers. Thanks

Post a Comment

<< Home